Publication time acts as a snapshot for scientific work. Whether a project is ongoing or not, work which was performed months ago must be described, new software documented, data collated and figures generated.

The monumental increase in data and pipeline complexity has led to this task being performed to many differing standards, or lack of thereof. We all agree it is not good enough to simply note down the software version number. But what practical measures can be taken?

The recent publication describing Kallisto (Bray et al. 2016) provides an excellent high profile example of the growing efforts to ensure reproducible science in computational biology. The authors provide a GitHub repository that “contains all the analysis to reproduce the results in the kallisto paper”.

They should be applauded and indeed - in the Twittersphere - they were. The corresponding author Lior Pachter stated that the publication could be reproduced starting from raw reads in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive through to the results, which marks a fantastic accomplishment.

Hoping people will notice https://t.co/qiu3LFozMX by @yarbsalocin @hjpimentel @pmelsted reproducing ALL the #kallisto paper from SRA→results

— Lior Pachter (@lpachter) April 5, 2016

They achieve this utilising the workflow framework Snakemake. Increasingly, we are seeing scientists applying workflow frameworks to their pipelines, which is great to see. There is a learning curve, but I have personally found the payoffs in productivity to be immense.

As both users and developers of Nextflow, we have long discussed best practice to ensure reproducibility of our work. As a community, we are at the beginning of that conversation

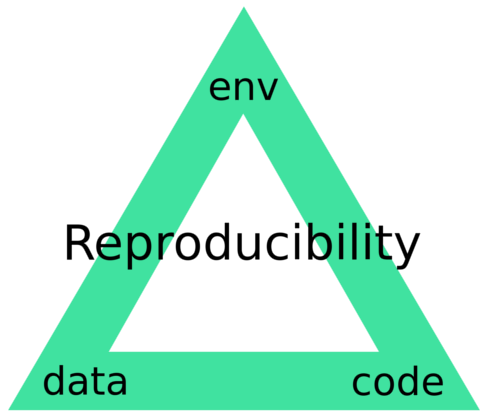

This is our goal. It is one thing for a pipeline to be able to be reproduced in your own hands, on your machine, yet is another for this to be guaranteed so that anyone anywhere can reproduce it. What I mean by guaranteed is that when a given pipeline is executed, there is only one result which can be output. Envisage what I term the reproducibility triangle: consisting of data, code and compute environment.

Figure 1: The Reproducibility Triangle. Data: raw data such as sequencing reads, genomes and annotations but also metadata such as experimental design. Code: scripts, binaries and libraries/dependencies. Environment: operating system.

If there is any change to one of these then the reproducibililty is no longer guaranteed. For years there have been solutions to each of these individual components. But they have lived a somewhat discrete existence: data in databases such as the SRA and Ensembl, code on GitHub and compute environments in the form of virtual machines. We think that in the future science must embrace solutions that integrate each of these components natively and holistically.

Nextflow provides a solution to reproduciblility through version control and sandboxing.

Version control is provided via native integration with GitHub

and other popular code management platforms such as Bitbucket and GitLab.

Pipelines can be pulled, executed, developed, collaborated on and shared. For example,

the command below will pull a specific version of a simple Kallisto + Sleuth pipeline

from GitHub and execute it. The -r parameter can be used to specify a specific tag, branch

or revision that was previously defined in the Git repository.

nextflow run cbcrg/kallisto-nf -r v0.9

Sandboxing during both development and execution is another key concept; version control alone does not ensure that all dependencies nor the compute environment are the same.

A simplified implementation of this places all binaries, dependencies and libraries within

the project repository. In Nextflow, any binaries within the the bin directory of a

repository are added to the path. Also, within the Nextflow config file,

environmental variables such as PERL5LIB can be defined so that they are automatically

added during the task executions.

This can be taken a step further with containerisation such as Docker. We have recently published work about this: briefly a dockerfile containing the instructions on how to build the docker image resides inside a repository. This provides a specification for the operating system, software, libraries and dependencies to be run.

The images themself also have content-addressable identifiers in the form of digests, which ensure not a single byte of information, from the operating system through to the libraries pulled from public repos, has been changed. This container digest can be specified in the pipeline config file.

process {

container = "cbcrg/kallisto-nf@sha256:9f84012739..."

}

When doing so Nextflow automatically pulls the specified image from the Docker Hub and manages the execution of the pipeline tasks from within the container in a transparent manner, i.e. without having to adapt or modify your code.

Data is currently one of the more challenging aspect to address. Small data can be easily version controlled within git-like repositories. For larger files the Git Large File Storage, for which Nextflow provides built-in support, may be one solution. Ultimately though, the real home of scientific data is in publicly available, programmatically accessible databases.

Providing out-of-box solutions is difficult given the hugely varying nature of the data and meta-data within these databases. We are currently looking to incorporate the most highly used ones, such as the SRA and Ensembl. In the long term we have an eye on initiatives, such as NCBI BioProject, with the idea there is a single identifier for both the data and metadata that can be referenced in a workflow.

Adhering to the practices above, one could imagine one line of code which would appear within a publication.

nextflow run [user/repo] -r [version] --data[DB_reference:data_reference] -with-docker

The result would be guaranteed to be reproduced by whoever wished.

With this approach the reproducilbility triangle is complete. But it must be noted that this does not guard against conceptual or implementation errors. It does not replace proper documentation. What it does is to provide transparency to a result.

The assumption that the deterministic nature of computation makes results insusceptible to irreproducbility is clearly false. We consider Nextflow with its other features such its polyglot nature, out-of-the-box portability and native support across HPC and Cloud environments to be an ideal solution in our everyday work. We hope to see more scientists adopt this approach to their workflows.

The recent efforts by the Kallisto authors highlight the appetite for increasing these standards and we encourage the community at large to move towards ensuring this becomes the normal state of affairs for publishing in science.

Bray, Nicolas L., Harold Pimentel, Páll Melsted, and Lior Pachter. 2016. “Near-Optimal Probabilistic RNA-Seq Quantification.” Nature Biotechnology, April. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/nbt.3519.

Di Tommaso P, Palumbo E, Chatzou M, Prieto P, Heuer ML, Notredame C. (2015) “The impact of Docker containers on the performance of genomic pipelines.” PeerJ 3

doi.org:10.7717/peerj.1273.Garijo D, Kinnings S, Xie L, Xie L, Zhang Y, Bourne PE, et al. (2013) “Quantifying Reproducibility in Computational Biology: The Case of the Tuberculosis Drugome.” PLoS ONE 8(11): e80278. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080278